Ever wondered why there are two types of open G chord? Or why some chords have crazy names like m7b5#11 (and what all those letters even mean)?

Just because we rely on shapes to learn chords on the guitar doesn’t mean it’s difficult to understand these symbols.

In fact, after reading through this article, you can even use these descriptive chord names to help yourself learn a song, simplify a song or adjust a chord to suit your preferences.

I promise, it’s nowhere near as complicated as it seems!

What is a guitar chord?

Guitar chords, like chords on most other western instruments, are a collection of notes that we use to create music.

They can be played as a strummed chord, but it’s also accurate to describe an arpeggio of three or more notes as a chord too (for example, when we pick through the notes of a chord shape rather than strumming) so they are used by lead players too.

Here is a guide to help you work out chord shapes all over the fretboard if you need some practical help before delving into this topic.

Major and Minor Chords

The most common types of chords we play on the guitar are major or minor chords.

Any time you play a G chord, that’s technically a G major chord. Am is A minor and so on.

Both types of chords are what we call ‘triads,’ meaning they’re made up of three notes.

Major Guitar Chords

If we take C Major as our example, it is made up of the following three notes from the C Major scale:

C - E - G

The C is the root note, or the first note from the C Major scale.

The E is the 3rd note from the C Major scale.

The G is the 5th note from the C Major scale

Remember it this way: a major chord is made up from the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes of the root major scale.

‘But wait,’ I hear you say; ‘when I play a C Major chord, I’m playing 5 notes!’

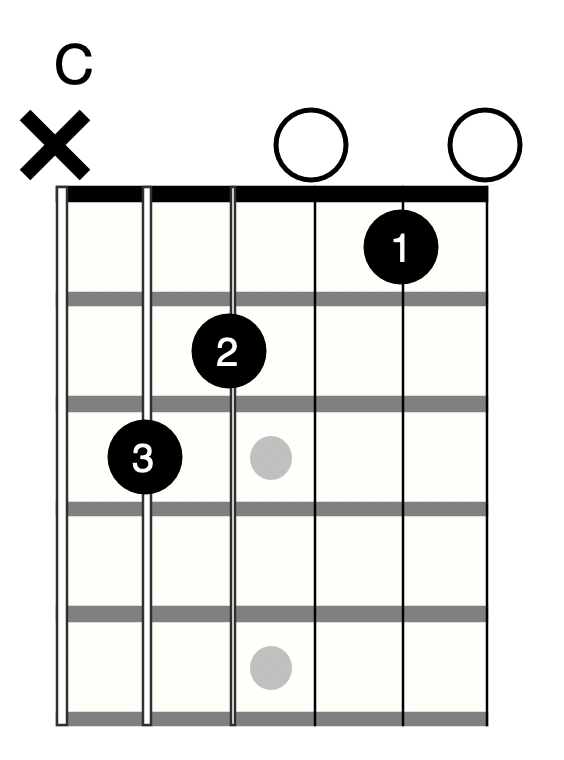

That’s true if you play your C chord like this:

However, if we look at the notes you’re playing in this C Major chord, you’re playing:

1st string: E

2nd string: C

3rd string: G

4th string: E

5th string: C

In total, we’re still only playing the notes C, E and G, which means we’re still just playing a C Major chord, because you can double up as many notes as you want. If I had a 20 string guitar, I could play 18 C’s, one E and one G and I would still be playing a C chord.

If you need a bit of help with the notes, check out this guide to learning the guitar fretboard.

Minor Guitar Chords

To convert a major chord to a minor chord on the guitar, all I have to do is flatten the 3rd note.

For example, C Minor has the notes:

C - Eb - G

which is the 1st, flat 3rd and 5th notes from the C Major scale. Alternatively, you could think of it as the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes from the C Natural Minor Scale, but I find it easier to relate everything to the major key (and that’s what I’ll stick to for the rest of this article to streamline things - if you prefer to think the minor way that’s totally fine though).

Note that the 3rd note isn’t necessarily a flat, it’s just flat compared to the original note.

For example, a D Major chord has the notes:

D - F# - A

which are the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes from the D Major scale.

D Minor therefore has the notes:

D - F - A

as when we flatten the F#, it becomes F.

Of course, in practice, we often have to re-arrange the shape completely to make it possible for our fingers to play the chord, but musically, we’ve only ever adjusted one note by one fret to change from major to minor.

Diminished and Augmented Guitar Chords (dim, °, aug, +)

The other types of triads we play on the guitar are diminished and augmented chords.

These don’t feature in pop and rock much, but certain styles (Classical, Metal, Jazz, film scores etc) will use these chords sparingly for a nice effect as they have a very distinctive sound.

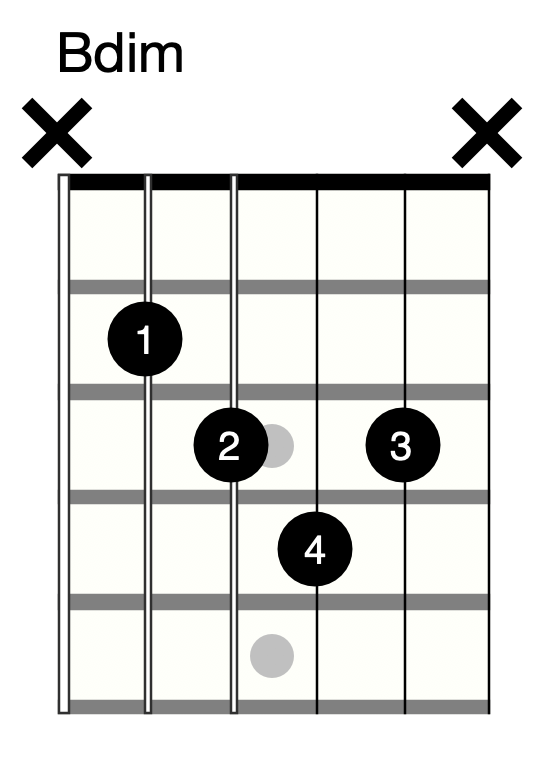

Diminished chords will typically look like this:

Cdim or C°

and are made up of the 1st, flat 3rd and flat 5th of the root major scale.

Cdim, for example, would be:

C - Eb - Gb

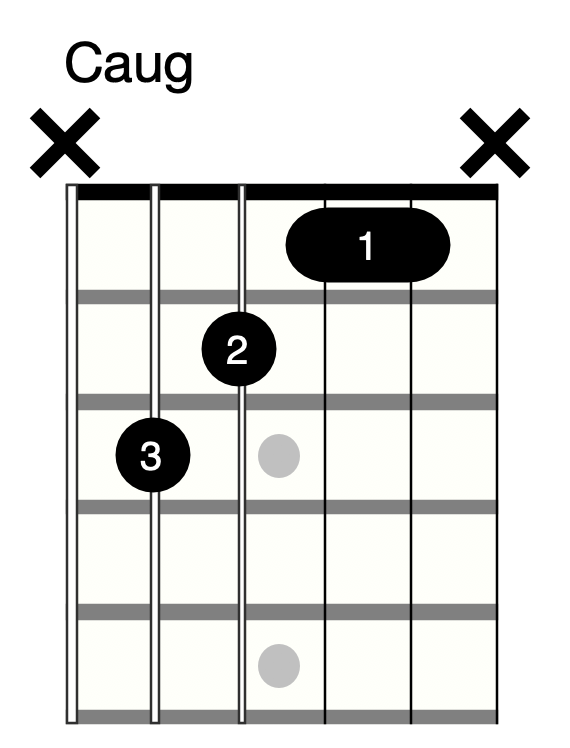

Augmented chords will typically look like this:

Caug or C+

and are made up of the 1st, 3rd and sharp 5th of the root major scale.

Caug, for example, would be:

C - E - G#

Both types of chords are a bit fiddly to play on the guitar due to our tuning system, so you’ll likely use a shape that’s song dependent or only play a few notes on the guitar when playing diminished or augmented chords, but otherwise they work exactly the same way as our major and minor triads.

Power Chords (5)

Power chords (or 5 chords, as they are more accurately called) only have two notes in them, which makes them super easy to play on the guitar and super versatile too. They also sound great with distortion, especially compared to open chords.

They’re usually written like C5 or Bb5 but you’ll also see them written out in tabs all the time, as many rock guitarists prefer to work with tabs rather than chord names when starting out.

A 5 chord is made up of the 1st note from the major scale and the 5th note from the major scale. That’s where the 5 in the name comes from - all we have is the root note and the 5th.

For example, a C5 chord would be:

C - G

By leaving out the 3rd, we’ve left out the important note that tells us whether the chord is major or minor, which means that you can swap any major or minor chord for a power chord and it should work fine. Of course, by leaving out that note, you will have simplified the song a bit, so it may sound a bit too basic, but it shouldn’t sound “wrong”.

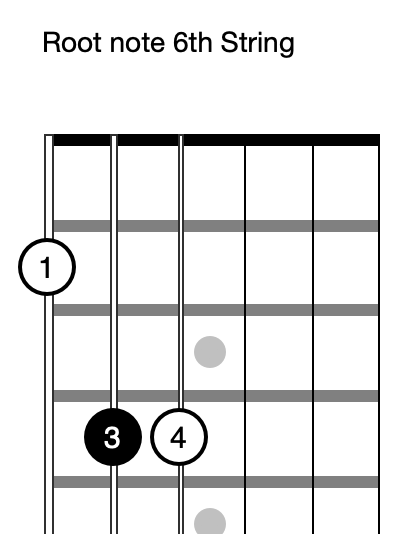

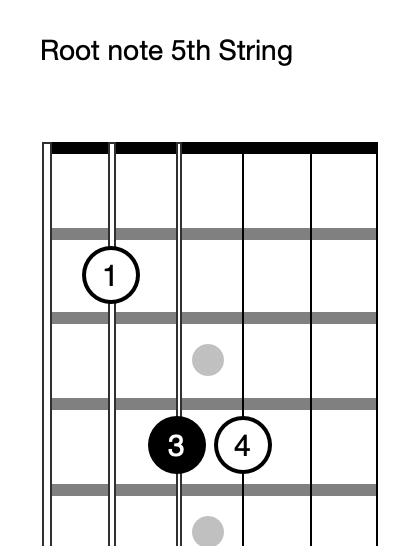

We usually play power chords as one of these shapes:

The first two shapes have the root note doubled up, whereas the second two shapes just include the root and the 5th, but both are fine to play.

You can definitely play 5 chords other ways though, so long as you only include those two notes. As soon as you add another note, you have to rename it.

Sus Chords (sus2, sus4, sus)

Suspended chords, or sus chords, are similar to the power chord in that they leave out the 3rd note from the chord. However, sus chords add in a new note to replace the missing 3rd.

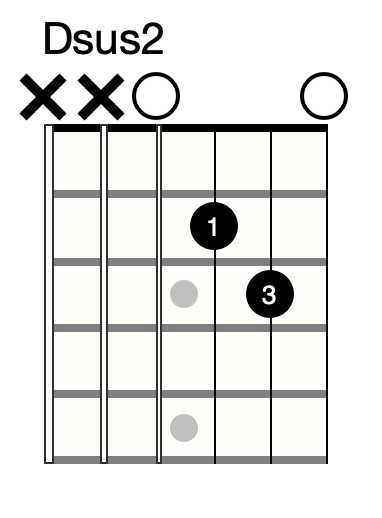

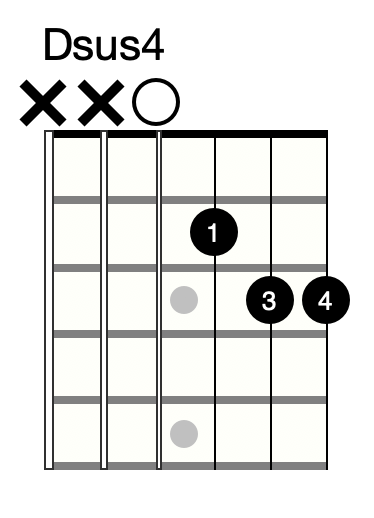

They can be written as Dsus2, Csus4, Asus or sometimes, less accurately D2, C4. (I won’t go into why those options are bad ways to describe the chords for now - let’s save my opinions for another article!)

A sus2 chord replaces it with the 2nd note from the major or minor scale, so is made up of the 1st note, 2nd note and the 5th note from the scale.

For example, Csus2 would be:

C - D - G

A sus4 chord replaces it with the 4th note from the major or minor scale, so is made up of the 1st note, 4th note and the 5th note from the scale. In general, if someone just says “sus” they mean a sus4 chord, but if you are ever writing out chords yourself, do your fellow guitarists a favour and specify which one you mean as it can be ambiguous.

Sus chords are great for adding suspense, suspending the listener just a little movement away from a major or minor chord. They work really well immediately before or after the parallel major or minor chord - for example, if you have just played a D chord, you could then play a Dsus2 and then a Dsus4.

6 Chords (6, min6)

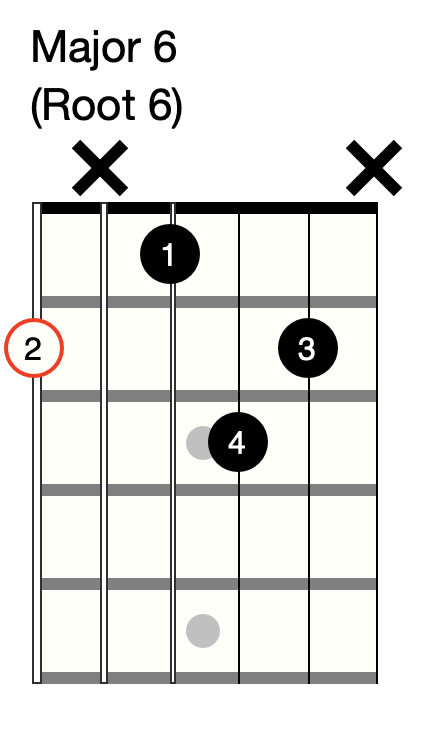

6 chords are just major or minor chords with the 6th note from the major scale added on.

They’re usually written as C6 or Cmin6 depending on whether you are adding the 6th to a major or a minor chord, but the 6th is always the 6th note from the major scale, not the minor scale. They can also be written out as Cmaj6 or Cmin(maj6) respectively.

For example, a major 6 chord would have the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 6th notes from the Major scale.

C6 would therefore be:

C - E - G - A

Root note is in red.

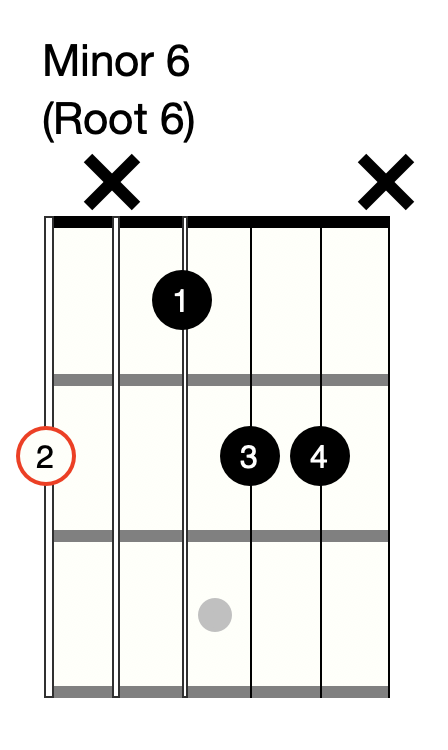

A Minor 6 chord would have the 1st, flat 3rd, 5th and 6th notes from the Major scale.

Cmin6 would therefore be:

C - Eb - G - A

Root note is in red.

7th Chords (7, maj7, min7, dim7, min/maj7, half-diminished, min7b5, +maj7)

7th chords add the 7th note from the major scale to a triad, but the type of 7th can vary depending on which 7th chord you’re playing.

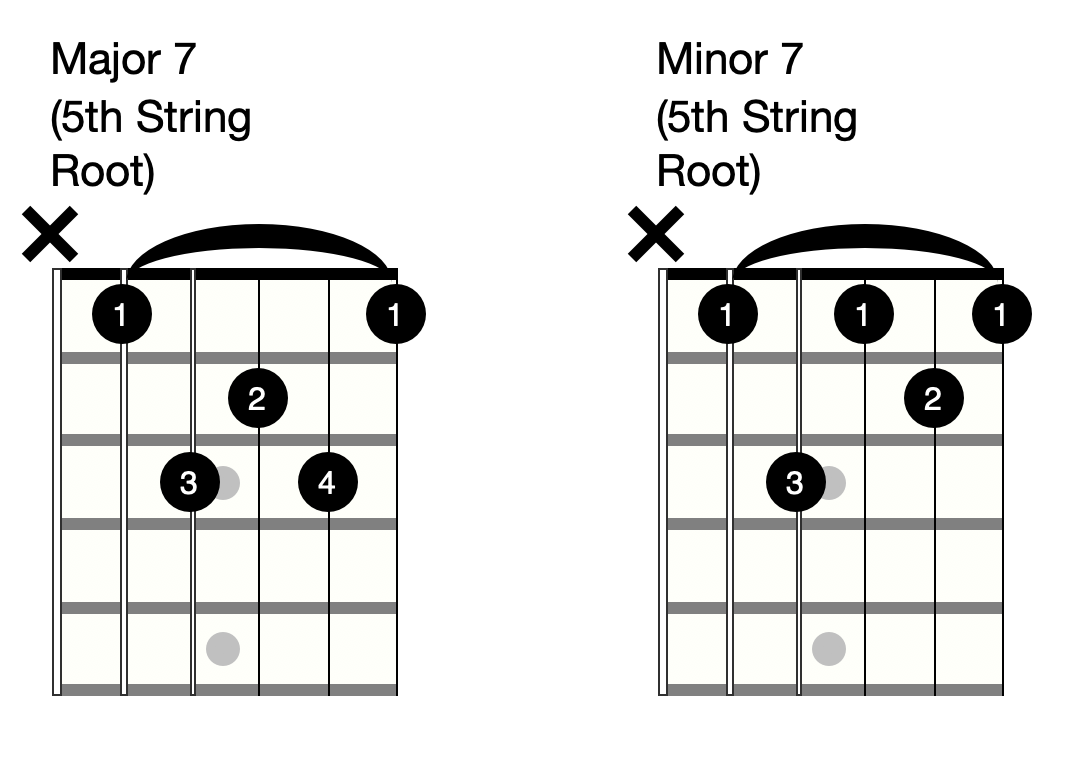

Major 7 chords (maj7, Δ, M7) use the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th notes from the major scale.

For example, Cmaj7 is:

C - E - G - B

Dominant 7 chords (7) use the 1st, 3rd, 5th and flat 7th notes from the major scale.

For example, C7 is:

C - E - G - Bb

Minor 7 chords (min7, -7, m7) use the 1st, flat 3rd, 5th and flat 7th notes from the major scale.

For example, Cm7 is:

C - Eb - G - Bb

Diminished 7 chords (dim7, °7) use the 1st, flat 3rd, flat 5th and double flat 7th from the major scale.

For example, Cdim7 is:

C - Eb - Gb - Bbb*

*Bbb is the same note as an A, but we call it Bbb so that it remains a 7th and not a 6th note from the major scale. Confusing name, simple to play.

Minor/Major 7 chords (min/maj7) use the 1st, flat 3rd, 5th and 7th notes from the major scale. It’s basically a minor triad with the major 7th added to it.

For example, Cmin/maj7 is:

C - Eb - G - B

Half-diminished 7th, or minor 7 flat 5 chords can be written and described in quite a few ways depending on the style you’re playing.

In classical, they’ll be called ø7 or just ø, whereas in contemporary music and jazz they’ll usually be written as min7b5 or m7b5.

The chord is the same either way, but the jazz name gives you more clues as to what notes we’re playing, so I’ll stick to that name from now on (m7b5).

The Minor 7 flat 5 chord uses the 1st, flat 3rd, flat 5th, flat 7th from the major scale.

For example, Cm7b6 is:

C - Eb - Gb - Bb

Finally, Augmented Major 7th (+7, Cmaj7♯5, augmaj7) chords use the 1st, 3rd, sharp 5th and 7th notes from the major scale. Again, the jazz name, Cmaj7#5 is the most descriptive so therefore the easiest to remember.

For example Cmaj7#5 is:

C - E - G# - B

In practice, you’re mostly going to see Maj7, Min7 and 7 chords coming up, but the m7b5 does come up a lot in jazz and a few other styles. There are other 7th chords that could theoretically exist too, but we’ll get to the them in altered chords below as they’ll typically be written differently.

Add chords (add9, (11))

Add chords are super easy to understand once you work out what the numbers are talking about.

All you need to do is take the basic major or minor chord and add the note specified.

This can be written two ways:

Cadd9 or

C(9)

By putting the extra number in brackets, you’re saying “add this note”. This would be different to a C9, which we’ll look at later under extensions.

Let’s look at some options by first writing out all of the possible chord tones in C Major.

C - E - G - B - D - F - A

if we write these out as scale degrees, these would be:

1 - 3 - 5 - 7 - 9 - 11 - 13

So, if we wanted a Cadd9, we take the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes from the major scale as normal, then add the 9th note.

C - E - G - D

That’s it!

I won’t give you guys example shapes of the chords from here on out as there are way too many options. Just remember that you can’t include any extra notes or you’ll change the chord again.

If you do want to add multiple notes, you could use a Cadd9add11, or C(9,11), which would have the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 9th and 11th notes from the C major scale, for example.

C - E - G - D - F

Chord Extensions (9, 11, 13, m9, m11, m13, maj9, maj11, maj13)

Extensions are 7th chords that have been “extended” with extra notes beyond the 7th.

They’re most commonly based on a major 7, minor 7 or dominant 7 chord, so you will see something like maj9, M11, maj13 for the ones based on a major 7th chord, m9, minor11 or -13 for ones based on a minor 7th chord, and 9, 11 or 13 for the ones built on a dominant 7 chord.

If we look at our possible chord tones in C Major again:

C - E - G - B - D - F - A

and in scale degrees, these would be:

1 - 3 - 5 - 7 - 9 - 11 - 13

we can see our standard extensions are the 9, 11 and 13.

The basic rule is this: you must include all lower numbers for a chord extension. This is different to the add chords above, where we just added the notes specified.

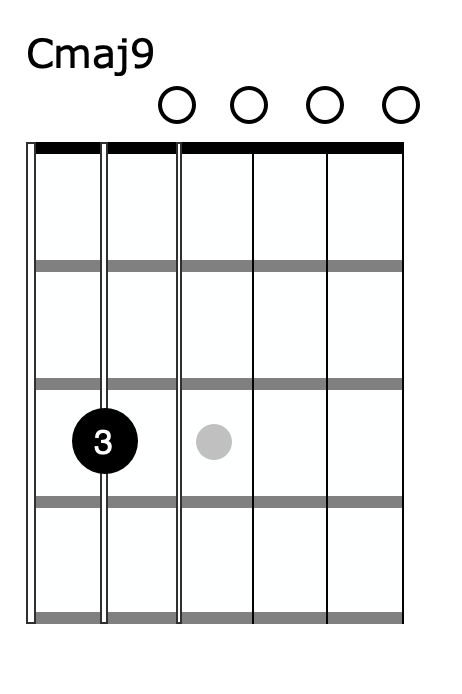

For example, a major 9 chord uses the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th and 9th notes from the major chord.

Cmaj9 would therefore be:

C - E - G - B - D

Major 11 chords use the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th and 11th notes from the major chord.

Cmaj11 would therefore be:

C - E - G - B - D - F

Finally, Major 13 chords use the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th and 13th notes from the major chord - effectively an entire major scale in one chord.

Cmaj13 would therefore be:

C - E - G - B - D - F - A

If you want to change any of these to minor or dominant extension chords, you just have to change the 3rd and the 7th as discussed in the 7th chords section above - the 9th, 11th and 13th remain the same.

Now, you’ve probably realised the problem we have on the guitar with playing a 13 chord (or even sometimes an 11 or 9). We can’t reach all of those notes at once unless we add more strings!

To solve this problem, and to make the chord sound a bit nicer, we often leave out certain notes to make the chord both playable and fit the song better.

Easy notes to leave out are the 5th, then the extensions underneath (maybe leave out the 9th if you are doing a 13th, for example), and sometimes even the root note, but it depends a lot on the song.

For me, if I see a Cmajor13 in a song, I would pick whichever extension I think best suits the song. Sometimes I’d even leave out the 13th, which isn’t technically correct, but may mean the difference between a smooth chord movement and an impossible one if the song wasn’t originally composed for guitar.

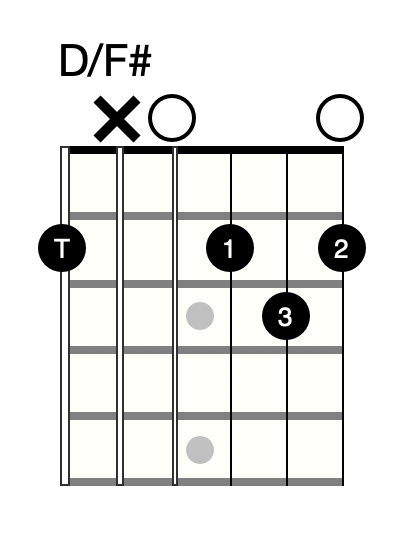

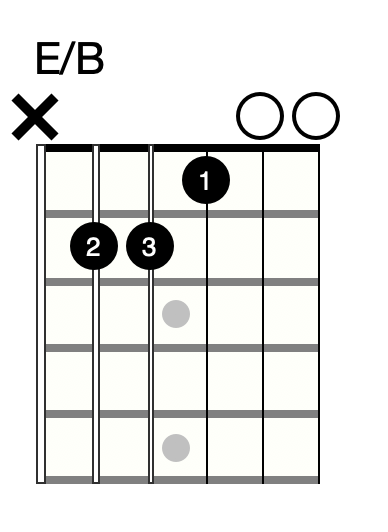

Slash Chords (D/F#)

Slash chords are commonly referred to as inversions on other chordal instruments, which basically means we are mixing up the order of the notes in the chord to get a different sound.

In practice, we are playing inversions all the time on the guitar already, as it’s often difficult to play the notes in order from highest to lowest as we only have so many fingers available (compared to piano, for example).

What slash chords are telling us is the chord we are playing (the letter on the left) and the bass note we should be playing (the letter on the right).

For example, D/F# means play a D chord, but make sure the lowest note you play is F#.

D (chord) / F# (bass note)

It is not a mix of the two chords, as it’s still a D chord - we haven’t added any notes from an F# chord.

Sometimes, you’ll play this by adding a note to the chord, or it could be by playing the chord from a different string like the two examples below.

When in doubt, remember that the left hand side, the chord name, is the more important part. If you play the correct chord by don’t play the bass note recommended, it’s not a huge deal - especially if you’re playing with a bass player.

In both of the above examples we haven’t actually added any new notes to the chord itself - D major already has an F# in it after all. It is possible to add a base note that wasn’t part of the original chord though. The process is exactly the same.

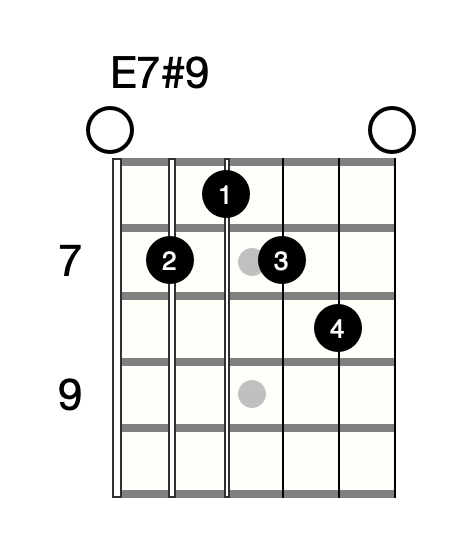

Altered Chords

Altered chords are where we take any of the above chord types and change one or more notes.

They’re super easy to understand if you’ve followed everything up to this point, as they tell you in the name which note to change.

For example, E7#9 is just an E7 chord with a #9 added to it. The “altered” part is the #9. It is made up of the 1st, 3rd, 5th, flat 7th and sharp 9th from the E major scale.

E - G# - B - D - F##*

*Note that F## is the equivalent of G - we just need to call it F## so it remains a 9th and not a 10th or a flat 3rd, which would be more confusing to understand.

There are so many options for altered chords, but just remember - the name is telling you what to do. Read it left to right, write down the notes and you’ll understand what it means pretty quickly.

Working out your own chords

The nature of chord theory is that there will be multiple ways to describe each chord, but the aim is to find the most logical, clear and accurate description so that players can know:

What function the chord has in the song

How to play the chord

What they can substitute the chord for (if it’s hard to play or not sounding great on their instrument)

Because if this, you’ll find all sorts of interpretations in chord charts and Youtube videos. Focus on understanding what the chord is, what notes make it up and the differences between each one and you’ll be able to make your own judgements as to how best to play (or describe) any chord that comes up.

A great way to understand all of this chord knowledge is to use it to write your own guitar songs.

And remember - you don’t need to be an expert at all of the chords listed above. Focus on the ones that come up in your playing regularly, or the ones you like the sound of the most and build your understanding from there.